“Running an ultramarathon is like putting your life on the shelf and experiencing it anew in an entire day.”

It happened by chance – I asked my dad in August 2023 if I could borrow his Specialized road bike that hung in his garage like a trophy, collecting dust. I took custody of his beloved “FedEx” bicycle, the frame bearing the company’s talismanic orange, blue, and white colors. He had kept the bike in great condition. It was rideable immediately, but just needed some tailoring to fit my own ergonomics.

I purchased new clipless pedals and cleats in October 2023 and started riding on the road in earnest… well, not immediately. While climbing the street leading back to my place just after leaving the bike shop, I shifted improperly and wedged my chain stuck between my bottom bracket and chainring, temporarily taking the bike out of commission. I still had a lot to learn about my dad’s bike.

Gradually replacing some of the older components as they showed their age; the tires, brake cables, brake pads, bar tape, and chain – I developed a deeper fondness for my dad’s longtime recreational vehicle. It still held firm after 20+ years of wear, and with a bit more care, it became a smoother ride too.

Almost a year after reviving the bike and 3500 km later, I participated in Foxy’s Fall Century up in Davis. It was my first century, and the event captured everything great about bicycling – companionship, camaraderie, nature, and achievement. I was hooked. So when Davis’ Bike Club’s other premier annual event, the Davis Double Century, was nearing closer, I knew that I wanted to partake and to experience bicycle riding on a grander scale. It would be a massive, 312 km, 2700m elevation gain, single-day tour-de-force. However, it would certainly be a leap from my current abilities, given that my longest ride at that point had only totaled 110 km. Maybe I had bitten off more than I could chew, but the only way to find out would be a trial by fire.

As the days ticked away leading up to the Double Century, I was filled with a burgeoning sensation of excitement and anticipation. I’d never shied away from challenges, but I wasn’t sure how to prepare for this one. I decided to keep things simple. I’d pack light: a handful of gels, some salt sticks for electrolytes, and a portable battery to recharge my headlight, taillight, and smartwatch. My bike had been squeak-squeaking away the entire week, so for only the second time ever, I futzed around with my idle cleaning supplies, wiping out the accumulated grime from every corner of the frame that I could reach. I finished with some chain degreaser and some lube, and after a few test pedal strokes up and down the block, the ride felt much more seamless. Satisfied, I wiped away any residue and moisture off of the bike. It was going to be a good day.

After de-boarding the train in Davis, it was a short 5 km, 15 minute ride to the nondescript motel where I’d attempt to muster all the Zs that I could. The tarmac leading eastwards to my accommodation was in good shape, but questionable debris and goat heads on the shoulder threatened a nasty surprise. I cut inwards off of the shoulder – I hadn’t brought any paraphernalia for fixing a flat. A puncture would be terminal, so handling the bicycle with focus was the utmost priority.

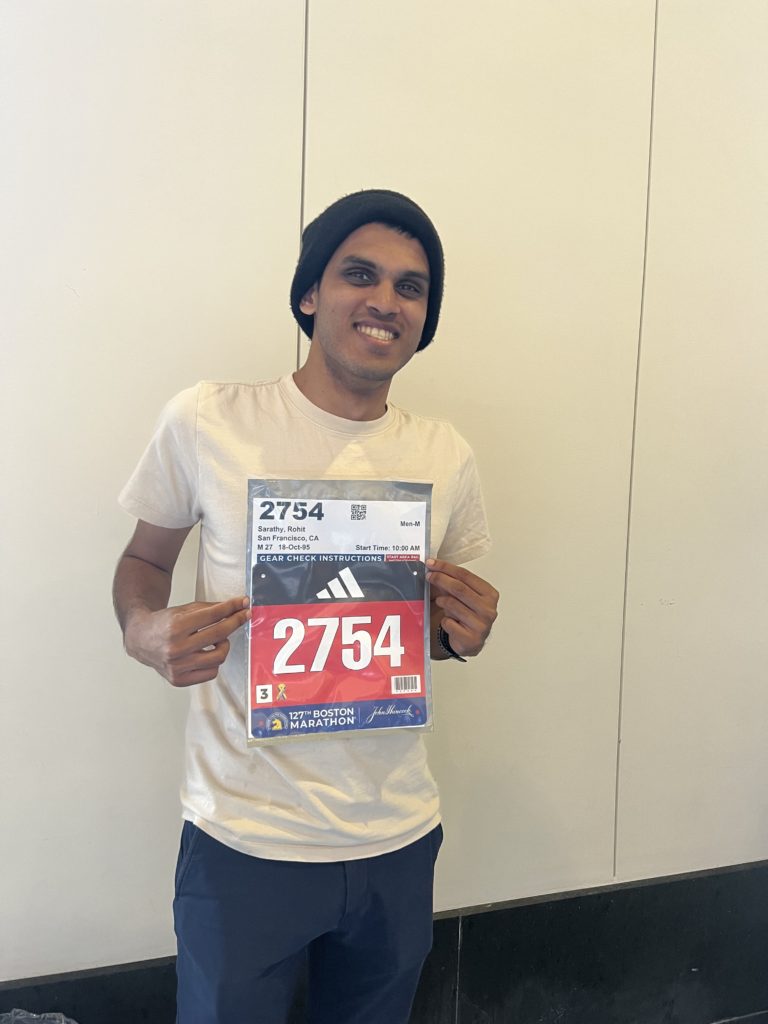

Getting up at 03:15, I treated myself to a quick shower to wake myself up. It was going to be a long day. I slipped on my jersey and my bib, rolling out my bicycle down the motel’s stairwell. It was a gentle 6.5 km ride to the call spot, and I used the “neutral section” spin to get a feel for my form on my bike. Sharp breezes rustled fallen leaves on the side of the road, disrupting what was otherwise a quiet night. Claiming my bib from the check-in, I left a bag of non-essentials at the Veteran’s Memorial Center. I wanted to carry as little weight as possible on the roads. Every extra gram toted along would compound over the entirety of the day.

“It isn’t the mountains ahead to climb that wear you out, it’s the pebble in your shoe.”

-Muhammad Ali

I finally started my watch and rolled out on the roads at 04:20, a little later than I would have liked. My primary goal was to finish the event and to make it home safely, but my stretch goal was to catch progressively earlier trains back to San Francisco if my abilities permitted. Even though it would be a 15 hour ordeal, every minute was still worth its weight in gold. I had to keep moving.

The rural roads leading out of Davis were dark and unlit, save for the occasional passing car. My front light illuminated a 60 degree cone, allowing good head-on visibility but limited peripheral capability. A lapse in awareness on turns and corners could mean putting my front wheel into an obscured pothole, potentially minimizing a gran fondo into a ten-minute nothingburger.

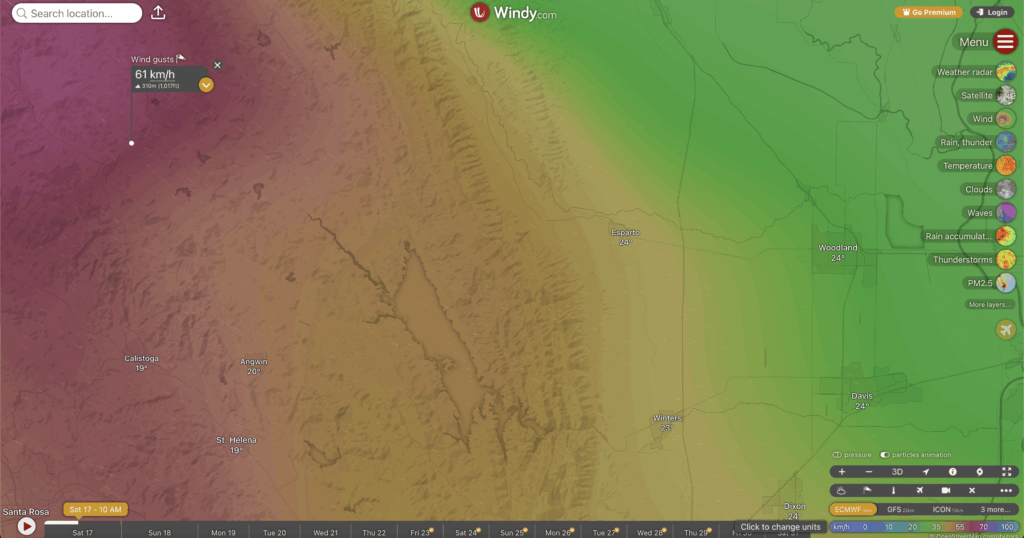

The lede early on was the monstrous gusts that swept across the roads. I caught up with a pair of experienced riders, and we struck up a congenial conversation as we shared turns pulling at the front. However, the crosswinds had claimed its first victim, sending one of my fellow rider’s wheels into a sizable hole just 5 km from the start. His wheel went flat a few kilometers later, and we huddled on the shoulder while he rapidly inflated a spare tube. Less than five minutes later following a most impressive pit stop, we were all riding again, the banter flowing smoothly between us.

As soon as we crossed CA-113 onto the rural roads, the winds blustered across with such force, threatening to knock the hardiest riders off of their bikes. As my new friends took a nature break, I decided to continue riding, and lunged forward towards the next knot of riders. The winds were blowing almost true north early on, creating strong crosswind gusts while we headed westbound. It was a short but welcome reprieve when we turned left to head south for a few kilometers, freewheeling and enjoying the tailwind in the process. However, once we exited the first aid station just outside of Lake Berryessa, the wind returned with interest, now coming from the northwest directly in front as we climbed towards Monticello Dam.

CA-128 winded slightly leading us into a secluded Stebbins Canyon, with the dam looming like an impassable wall in front of us. A short bridge leading into a hairpin saw us cut through Solano County, albeit for just a few minutes. The canyon’s sides shielded us from the constant winds and allowed us some time in seclusion to work the relatively gentle gradients up to the first false flat near the Glory Hole. After cresting the summit of Cardiac Hill, the day’s first major climb, I treated myself to a Hammer espresso gel. The shot of caffeine provided a much-needed wake-up slap, and I used the jolt of energy to descend from the apex with more intention deeper into Napa County.

Another gradual but sustained climb on 128 saw us negotiate a V-shaped bend, which had us facing into the teeth of the headwind once again. There were still another 30+ km to the next aid station and the winds had eroded my legs thoroughly. If this was how I was feeling barely a fifth of the way into the ride, I couldn’t fathom what the remainder of the day held in store for me. While on paper, the parcour leading to the Berryessa aid station seemed relatively controlled, it consisted of countless rolling hills. Headwinds negated the free kilometers that were supposed to be 50 km/h descents, dropping speeds down to 25 km/h. The wind ate at my legs some more, though there was next to nothing left.

I was relieved to see the white tent and plenty of other riders taking refuge from the gusts. I restocked my bidons with more LMNT and water, and some fizzy Hammer drink mix. I treated myself to a PBJ, some pickle spears, and a few watermelon slices. After a short bathroom break, I resaddled and continued on my way. The road pinched sharply after the second aid station into the distance, the crest of the climb invisible. I paced myself alongside a group of Filipino riders who always seemed to be in joyous spirits. Their infectious energy helped me tackle the immediate climb quickly before taking in a small descent into the triple digits. But around the 105 km mark, I could feel a cramp developing quickly in my right leg. I recognized the sinister feeling.

Seven months ago, I rode most of the Foxy’s Fall Century in my highest gear. The low pedal cadence exerted heavy pressure on my knees. Combined with poor refueling strategies, I cracked badly and imploded with less than 10 km to the finish. While riding off of the back of a racing club’s paceline, a sharp pain materialized in my upper right leg rapidly. Within seconds, it became excruciatingly painful to pedal, and I had to pull over to recuperate in a ditch for 10 minutes while my cramps subsided. I should have done my homework beforehand: the organizers sent a series of slides constituting a primer for tackling longer rides. One of the key pieces of advice was to keep pedaling cadence high, around 80 RPM, to stay loose throughout a long day of riding.

This time, there could only be one culprit, because I was already vigilantly monitoring my cadence and ensuring a healthy number of revolutions. Armed with the pattern recognition, I swiftly reached for my bidons and took a healthy swig of electrolytes. I backed off the fast pedaling cadence, and sure enough, the cramp and its indicia faded as quickly as they had appeared. I was able to continue riding without stopping at all.

Continuing past Pope Valley and into another series of climbs, I succumbed to taking multiple breaks while ascending. It was simply too much – the headwind was relentless, the roads were in horrendous shape, my legs felt weaker than paper, and ingesting fluids didn’t make me feel any better. I didn’t have an answer for how I was going to complete the next 190 km, let alone the bulk of the day’s climbs. I resigned myself to surrendering at the next rest stop.

Just past 135 km in the saddle, I realized how fatigued I was. I had been up since 3, and a wave of drowsiness punched me heavily in the face. I pulled over to a ditch just off of the road, laid my bicycle down on top of my legs, and took a short nap. Riders passing me checked in on me, asking if I was okay. I responded every time that I was fine, but internally, I was running on fumes. I didn’t know how much I had left, but at the pace I was going, the next aid station was half an hour away.

I managed to convince myself to get up and to continue moving until the next rest stop. Facing the fierce headwind again, I pedaled on low gears to keep my cadence high. I was moving at 17 km/h, the speed I’d normally climb a 3-4% hill at. Then, a miracle happened – I could hear a paceline approaching behind me. I let it pass and then bet the last tiny match I had to affix myself onto the back of the group. We moved considerably faster, closer to 22-23 km/h, but I was a lot more comfortable drafting. I was still well and truly cracked, but I wasn’t going to let the paceline slip until we reached the aid station.

The 8 kilometers to the third aid station in Middletown clicked away quickly, and soon enough, we were pulling into the recreation center for a much needed refuel. As I was laying down on the grass, contemplating whether I wanted to continue the ride, I remembered something that my uncle Kowsik had uttered many years ago.

“An ultramarathon… is an eating and drinking competition… with some running mixed in between.”

I was hungry! The aid station chief was very friendly and encouraging, and while stuffing myself silly with PBJs, Fritos, pickles, fruit, and Coke, I was able to find the will to resaddle my bike and to continue the ride. It was only 29 kilometers to the fourth aid station and lunch. However, the biggest climb of the day loomed ahead, as well as a mysterious 6.5 km gravel section. While my war with the wind was a losing battle, I was very fortunate to have not faced any major mechanical issues so far. The rural roads in Lake County were in even worse shape, with gaping cracks and rivets threatening terminal flats for the unaware rider.

The Big Canyon gravel sector arrived in short order, just a short 2 km from the Middletown rest stop. I had no experience riding gravel before (I didn’t count the 200m segmentette from the Golden Gate Bridge bikeway to the Presidio as part of my acumen), so my knowledge was solely based off of what I could glean from YouTube videos that I’d watched about the infamous Unbound race in Kansas. Generally, on gravel roads, there are much fewer lines to take because scree and other obstacles make different trajectories through the parcour untenable. I heightened my attention and sought to find these lines. Previous vehicular traffic had left some harder-packed pockets which were traversable at decent speeds. Whereas I’d previously been riding more upright and taking in scenery on the tarmacs prior, I focused more on the terrain 5-10 meters ahead, ensuring that I wasn’t rolling over larger or sharper rocks. Occasionally, a soft patch of sand on a given line would make putting down some power difficult, with my back wheel skidding and losing grip. However, these seemed to be the exception, and not the rule, and slowly but surely, I navigated the Big Canyon gravel more comfortably.

The gravel sector gave way to a paved, but bumpy road leading into the queen climb of the day. The tree cover became sparser, and while the ambient temperature was around 25 degrees, I could feel the asphalt absorbing more heat and baking me gradually. I sweated profusely. I took frequent breaks, not concerned with setting any VAM records. Slashing up the switchbacks with fellow riders, we skirted past the 100 mile mark. There was less than a kilometer left in the climb, and I could sense that the worse might be over. I willed my way to the crest, treated myself to some quick sips of electrolytes and water, and began my descent towards Clear Lake.

The descent into Lower Lake was not too technical, and I let the slightly banked curves pull me further, enjoying the free kilometers at speed. While checking the list of directions, a gust pried my cue sheet out of my hands and off of the road. Although I wasn’t having the best legs, I felt grateful that I’d had the foresight to print out a spare copy. After passing through the main intersection of the small town, the lunch stop was just a few pedal strokes away.

Catching up on my messages now that there was some cell service, it was 13:45 when I sat down for lunch. I had been on the road for more than 8 hours, and had been up for a few more than that. I treated myself to a roast beef sandwich before putting down another PBJ. After refilling my bidons and taking another moment of relief, it was time to resaddle and to face the last climbs of the day.

The next 10 kilometers remained miserable, with the headwind returning with a vengeance. To make matters worse, the route used CA-53’s meager shoulder which was littered with different hazards. Close-passing drivers changed the swirling wind vortices, threatening to throw me off balance. A group of triathletes could no longer sustain my ineptitude and passed me en masse. I held the back of their paceline’s wheel for another 10 minutes before succumbing to a softer pedaling cadence. In the distance, I could see the CA-53 and CA-20 intersection, a roundabout where we’d turn sharply right. I gritted my teeth and pedaled harder, confident that my fortunes would change with the difference in direction. I stuck my knee out cleanly and accelerated onto the CA-20 shoulder, dealing with the new pinch now in front of me. It didn’t matter how much I was aching anymore on this climb, because now that I was heading east, the gusts were no longer in my face.

CA-20 bisected the Cache Creek wilderness and the road presented a delicious descent leading to the last major climb of the day. I chased down fellow riders through the verdant landscape, keeping a vigilant eye on my watch for 197.3 – the distance marker of the door to the climb. It wouldn’t be a difficult one, just prolonged: 9.7 km @ 3%. I took frequent breaks, working in 5 minute bursts and then taking in some sips of electrolytes. The road was fully exposed, and I could feel the afternoon heat searing me more every minute. I wasn’t sure which gears felt comfortable anymore, and I shifted silly, trying to find the one that would move me up the slope the fastest. The highway twisted one more time and I could make out a tent on the side of the road. The aptly-named “Resurrection” rest stop came into view.

I coasted onto the pebbly gravel and racked my bike, fistbumping riders who had suffered the same conditions with me. Chatting with other riders about their experience throughout the day, I conveyed the magnitude of the morning and afternoon headwinds that we endured, and how it was soon to be a welcome tailwind. “After all we endured today? We fucking deserve it!” another rider remarked about the upcoming descent with a tailwind.

I pushed back from the rest stop 15 minutes later, just before 16:00. Continuing along CA-20 eastwards, I entered Colusa County, my fifth distinct county of the day. The next descent was the day’s sharpest, and injected a shot of adrenaline into my languishing body. The shoestring shoulder was bounded by a coarse rumble strip and debris on each side, with stiff girders bounding the edge of the road. This made the descent the most technical of the day, and I channeled every last iota of focus into gripping my handlebars firmly and anticipating the road’s curvature. I’d sneak a peek at my watch occasionally, which cheerfully informed me that I was gliding at 70 km/h. The air rippled my face, and tears streamed across my cheeks. I gently rested my fingers on both brakes, staying in a cramped aerodynamic position to preserve speed. The CA-20 / CA-16 junction appeared promptly and I took the necessary right turn briskly, coasting past a lone fire station in the wilderness.

I still had around 100 km to go, and could feel the cumulative weight and wear of the previous 9 hours in the saddle. The differences in pacing between all riders had compounded throughout the day, and I was at least 5 minutes in each direction from any peer. However, something during the descent on CA-16 made me forget all of the lingering pain that I had. Canyon walls on both sides towered over the meandering, two-lane highway. The tarmac was the best of the day, smoothly paved with minimal obstacles. A stream wended its way in the valley below, bubbling vigorously. Regal trees and shrubbery dotted the landscape. “Who cares if you’re in pain? You’re in a colosseum of nature, with the wind at your back, moving at 50 km/h. This is the way… this is better than the way!” I thought to myself. I felt one with the environment, interrupted seldomly by passing SAG vehicles monitoring our safety.

The road roughened somewhat meandering back into Solano County. The wilderness gave way to small pastures, ranches, and farms. I kept my cadence high and worked the lonely kilometers to the Guinda rest stop. Clumps of coasting riders appeared closer to the small town. The rest stop was nearby, and we soft-pedaled together into a small ranch that served as the aid station. I didn’t take as much time as the other stops, opting for a quick bidon refill, a fast PBJ, and a small pitstop.

I rolled out with a larger group of the Filipino riders and the Berkeley triathletes that had passed me earlier on CA-53. We formed an elongated paceline on the shoulder, with the front setting a brisk tempo early. Near the Cache Creek Resort, the shoulder abruptly disappeared, and I cut inside before disaster could strike. However, because of the rapid pace, I was now multiple bike lengths adrift from the paceline. I guarded my matches and let them float farther away. I wasn’t under any major time constraint anymore. I just needed to ensure that I finished around 20:45 so that I could catch the last Capitol Corridor home at 21:10 – easily doable at 20 km/h.

As CA-16 cut due east towards Esparto, my pace didn’t drop too much. I realized that while I could not hear it or see it around me, the winds were working in my favor now. Off of the highway now, the county roads presented an immense solitude. I felt lonely again, and fatigued. I focused on my parents’ faces mentally, imagining them willing me further. I thought of my late uncle’s soft smile, and felt his warmth guiding me forward. I kept moving, and with another zigzag on the county roads through town, I was pulling into the last rest stop of the day.

My watch battery indicated that it was running on borrowed time, and for the second instance, I admired the foresight that I had to lug my portable battery and my watch charger with me throughout the day. Perhaps a Strava activity only counts for clout, but I wanted to have the uninterrupted activity uploaded so that I could analyze my efforts later on. While waiting for my watch to collect a little more juice, I realized that there was a possibility I could make the earlier 20:10 train home if I rode quickly enough. It was 35 km to the finish, and I had an hour and twenty-five minutes, maybe a bit less than that, if I wanted to bank the extra hour. I hastily refilled my bidons once more and hit the road posthaste.

I needed to ride at 26-27 km/h on tired legs to make the earlier train home. At this point, my experience had firmly shifted to the Type II category, and I was overcome with a severe sense of summit fever. My legs were heavy, and no matter how much I tried to pick up the pace, my watch teased me saying that I was barely eclipsing 25. I fumbled my cue sheet on the road in a lapse of concentration. Cursing myself silently, I ambled back to pick it up. I didn’t have a bike computer, and my phone was tucked away, so my spare cue sheet was my only guide.

Suddenly, I heard a whizz akin to buzzing bees growing behind me. It was the group of Berkeley triathletes that I’d been yo-yoing with throughout the day, organized in their signature paceline again. I asked if I could join them for the last stretch, riding off the back. They happily agreed, and I slotted in behind their group. The tempo up front cranked another notch, with us now moving at 35 km/h back to Davis. My job became much easier, simply sitting on the last triathlete’s wheel in the draft.

The triathletes rotated their point person regularly, with the leader pulling for about 5 minutes at a time. Whenever the leader had finished their pull, I opened up a bike length for them to retake their place within their paceline. My watch clicked past 300, indicating that we had covered the last 5 km in about 8 and a half minutes. At this pace, there was only 20 minutes of riding left, and it was a straight shot back to Davis. There were more intersections and stoplights closer to the city, which would fragment the paceline temporarily. However, the group was committed to its synergy, treating their paceline as just another tempo workout. It quickly reformed again and we blitzed to the finish.

The last couple of kilometers felt ceremonial. The regimented paceline gave way to us riding side-by-side, coasting through suburban streets leading back to the high school. I thanked the triathletes for their graciousness, and we parted ways as we pulled into the VMC parking lot. I collected my drop bag and left VMC, eschewing the post-event buffet. I didn’t feel too hungry, and although I had thoroughly enjoyed my ride, I wanted to get home. Thanks to the triathletes’ blistering pace in the last 30 km, I had plenty of time to saunter from the finish back to the Davis train station. I racked my bicycle on the Amtrak and heaved a huge sigh of relief as it rolled along, allowing myself to process my thoughts from the entire day.

A ride isn’t over until you’re comfortably lying in your own bed, though, and the job wasn’t finished. Debarking the train at Emeryville, I started riding again and feeling a huge soreness in my arms. Presumably, the hours that I’d spent holding my hands in the drop bars had taken its toll. I wiggled them gently, heading south towards the West Oakland station. The temperatures south were considerably cooler, and cool Bay Area winds scratched through my jersey, making me miss the toasty valleys from the afternoon. While it had been a fortuitous day by most measures, my luck expired as I saw a homebound BART train pull away from the station just as I reached the faregates. I sighed and sank onto a hard platform bench, waiting for the next train to San Francisco.

The last mile leg from the San Francisco BART station back to my place was uncharacteristically uneventful. The headwinds that normally roar down my home street against an 8% climb took a much needed leave of absence, letting me work through the ultimate incline of the day in peace. I placed my bike inside the garage, slowly marched up the steps to my apartment, shed my backpack, and plopped myself onto a chair. It was 22:40, and the day was over. I felt an immense sense of gratitude, thankful for what my body had pulled out of the fire. I had seen a most beautiful swath of California in the process.

While my fitness left a bit to be desired, a myriad of other decisions swung firmly in my favor. I handled my bike with much more care, avoiding any punctures. I cramped just once, and when I did, I was able to make the necessary enroute adjustments to negate it. And just when I thought I was about to wave the white flag, I found a second wind that enabled me to triumph over the full distance.

Now I can’t say for certain if I’ll partake in another Gran Fondo of similar magnitude, but this Double Century practically happened on a whim. Who knows what the future holds!